NCAA Women’s Ice Hockey Coaches’ Attitudes and Knowledge About Concussions and Concussion Reporting

Marissa A. Gedman, MS, Kirsten D. Garvey, MS, Natalie A. Lowenstein, BS, Elizabeth G. Matzkin, MD

©2021 by The Orthopaedic Journal at Harvard Medical School

BACKGROUND Despite numerous mandates for education in the NCAA, it has been suggested that concussion knowledge is weakest in the coaching population. [British J Sports Med, 48(2):135-40 (2014)]. The purpose of this paper is to determine coaches’ knowledge and attitudes towards concussions in NCAA women’s ice hockey to elucidate a reason for the high rate of symptom non-disclosure in these athletes.

METHODS Data from an anonymous survey completed by 49 NCAA women’s ice hockey coaches were assessed for each coach’s self-reported history of diagnosed/suspected concussions and their prior reporting behaviors. Concussion history was used to compare attitudes/knowledge scores across coach respondents. Scores were calculated for coaches’ knowledge and attitudes using the concussion knowledge index score (CKI) and the concussion attitudes index score (CAI). Coaches also reported their institutions’ concussion education materials.

RESULTS 49/98 (50%) program surveys were completed. 67.3% of coaches reported having had a suspected/diagnosed concussion themselves and of those, ~24% of coaches did not report their concussions symptoms. (Mean CKI=27.78/45, about 62%; Mean CAI=15.22, an average of almost 51%) No significant differences in CKI and CAI scores were found when comparing coaches with differing concussion history or length of coaching experience. 96% of respondents reported “yes” to their institution having concussion management plans and concussion education.

CONCLUSION Coaches’ surveys reflected improving concussion education, potentially reflecting increased attention from academia, news and the medical field. 96% of NCAA institutions had concussion management plans and education programs. Average CKI was 62% and CAI was 51% suggesting room for improvement. Continuing education for coaches, athletes and team medical staff is imperative in preventing concussions and continued play in symptomatic athletes.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE Level V

KEYWORDS Concussions; women’s ice hockey; concussion reporting; ice hockey coaching; concussion knowledge; NCAA

The National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) injury surveillance indicates that women’s ice hockey has the highest concussion incidence rate across all collegiate female sports at 7.5 concussions per 10,000 athlete exposures.1 Recently, sports-related concussions have been the topic of numerous research studies, consensus statements, position papers and media reports.2 With this attention, there has also been a push for players and coaches to receive better education regarding concussions.

Despite the growing body of evidence to suggest that continued play while symptomatic can be extremely harmful later in life, studies across a range of populations continue to find that many athletes do not consistently engage in the important safety behavior of reporting symptoms of a possible concussion.3 Further, it has been shown that many athletes do not feel confident in their ability to report what they think may be a concussion symptom.4 Understanding what motivates athletes to report their concussion symptoms, or to not disclose symptoms, is critical in developing strategies for risk reduction, especially in contact sports, such as women’s ice hockey.5

One study found that 44.1% of reported concussions in women’s ice hockey during the 2014-2015 season were a result of player to player contact.6 Without legal body checking in the women’s game, the high number of player to player concussions suggests that more research is needed to determine what exactly is causing these collisions to lead to such a high incidence of concussions.

Although body checking is technically not allowed in a women’s ice hockey game, incidental and legal body contact is a frequent occurrence and is defined by USA Hockey as “contact that occurs between opponents during the normal process of playing the puck, provided there has been no overt hip, shoulder, or arm contact to physically force the opponent off the puck”.6 Many studies have found that even without body checking, approximately 50% of concussions in game situations in women’s hockey result from body contact between players.7-10

Sports related concussions are often difficult to diagnose because there is a dependence on the athlete to disclose his or her symptoms, which may be non-specific.6 The reporting behavior of an athlete is immediately influenced and impacted by their surroundings. This includes their teammates, coaches, parents and sometimes fans/boosters to their athletic team's program. Athletes are often presented with mixed messages of importance from their surroundings between their athletic performance and their safety.11 While this influential community has the potential to positively reinforce the importance of symptom reporting, it often has the opposite effect. A study done by Caron et al. found that former professional ice hockey players often hid concussion symptoms from teammates and coaches in an attempt to act in ways that they perceived to be “normative for their masculine sport culture”.12 Niven et al. referred to this pressure felt by athletes as the internal experience by an athlete to meet external demands.13

Another common pressure felt by athletes is from parents and coaches who innately control access to valued commodities such as playing time, scholarships, tuition money, and affection/affirmation.5 Due to these motivating pressures, as well as other factors, athletes often make the decision to return to play, even when feeling symptoms they know indicate a possible concussion. Kroshus et al. found that around half of the U.S. collegiate athletes in their study continued to play with symptoms of a possible concussion.5 Many studies have tried to identify a reason for between-individual variability in concussion reporting. Results range from the theory of planned behavior to Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory, but what is consistent across all models is the role a coach plays in an athlete’s environment and therefore, the athlete’s reporting behavior.14-17

The coach of a team holds control over the athletes simply by the commodities they have within their control. Athletes may feel pressure to not report their concussion symptoms because they may feel that they risk playing time and their spot in the line-up.5 For this reason, the coach and what he/she portrays to the athletes about concussion safety and symptom reporting is extremely pivotal in the athlete's decision immediately following a concussive blow. Many researchers have identified coaches as a key factor in the number of symptoms that go unreported simply because of the fact they make the line-up for competitions. It has been demonstrated that collegiate football players who perceived less support from their coach for appropriate concussion symptom reporting were more likely to continue play while symptomatic.25

Coaches can influence athletes in non-verbal ways, even when they are not overtly implying that they do not value concussion protocol or do not encourage symptom reporting. Many studies have covered the immense impact a coach-athlete relationship can have on injury reporting.26,27 This relationship is important to develop because athletes might mistake a coaches intensity or commitment to the team as a “win at all costs” mentality, inadvertently encouraging athletes to “suck it up” and play through injury.28,29

Current literature shows that while there is an abundance of research devoted to the epidemiology and prevention of concussions and head injuries, there is limited data on female athletes and specifically, female ice hockey players. Many studies cite female hockey players as an at-risk population for sport-related concussions but there is a lack of understanding as to what causes these athletes to sustain a high number of concussions compared to their male (and female) counterparts. Despite the high number of diagnosed concussions, it has been shown that 82.8% of college women’s ice hockey players did not report their concussion-like symptoms and continued to play on at least one occasion.6 Approximately 65% of athletes received pre-season concussion education, but further research is needed to increase the relationship between knowledge and education with reporting behavior.30 This study aims to analyze coaches’ concussion history and the effect it can have on their attitudes and education towards concussions in their players.

An anonymous online survey was completed by 49 NCAA women’s ice hockey coaches. Coaches reported their own concussion history as well as completing a concussion knowledge index and concussion attitude index questionnaire.18 In addition to these questions, coaches read brief scenarios and rated how they felt about them on a scale from strongly disagree (=1) to strongly agree (=7). These scenarios further exemplified the coaches’ feelings and attitudes towards concussions and the pressures associated with competitive sports and continuing to play through symptoms.

Approval by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board was obtained prior to the initiation of the present study and received exempt status (IRB# 2014P001782). Inclusion criteria were coaches actively rostered on a varsity NCAA ice hockey team. A recruitment email was sent to the head coach and athletic director of all NCAA participating colleges and universities with a varsity women’s ice hockey program. A total of 98 women’s ice hockey programs were contacted via email. The athletic director and head coach consented for the other coaches as well as the athletes to be contacted. One follow up email was sent to remind head coaches to respond to increase response rate. Study data were collected and managed using REDcap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools hosted by Partners HealthCare Research Computing, Enterprise Research Infrastructure & Services (ERIS) group. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies.6

Measures

Data was imported and reviewed using IBM SPSS 26.0 (IBMCorp). Analysis included demographic frequencies across all coaches, self-reported concussion history, concussion attitudes and concussion knowledge across all coaches who completed the survey. Scores were calculated for coaches’ concussion knowledge and attitudes using the concussion knowledge index score (CKI) and the concussion attitudes index score (CAI). The score averages (mean) were compared across coaches with and without concussion history as well as stratified by coaching experience. In addition to demographic questions, the survey aimed to measure coach’s knowledge and attitudes towards concussions. The survey contained 9 questions that addressed concussion knowledge and 6 questions that asked about attitudes towards concussions. Each question was scored on a Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree with strongly disagree equaling a score of 1 and strongly agree equaling 5. For the concussion knowledge questions, these values were adjusted based on whether the correct answer was strongly agree or disagree. With the data, we calculated a concussion knowledge index (CKI) and a concussion attitude index (CAI) for each coach that completed a survey. In total, the CKI scores can range from 9-45 and CAI scores range from 6-30.

Demographics

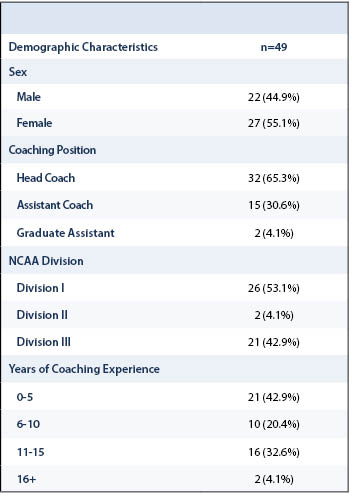

Ninety-eight programs were contacted, and 49 surveys were received from head coaches, assistant coaches and graduate assistants combined. If on average, women’s ice hockey coaching staffs have 2.3 (3 in division I, 2 in division II and III) coaches, the individual response rate was calculated to be about 22%. Table 1 shows the general demographic data collected from the participating coaches.

Concussion education materials

Coaches were asked to report on their institution’s concussion programs, and it was calculated that almost 96% of our respondents have both a concussion management plan as well as student-athlete concussion education provisions. (Table 2).

Coach personal concussion history

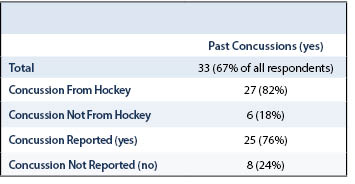

Sixty-seven percent of college coaches responding to this study have a personal history of a diagnosed concussion (Table 3). Although it is unfortunate that the majority have experienced a head trauma of some sort, it does give them a unique perspective on their players’ experiences with possible concussions. However, 24% of college women’s ice hockey coaches who participated in this study experienced a concussion and did not report their symptoms.

Coach Concussion Knowledge and Coach Attitudes Towards Concussions

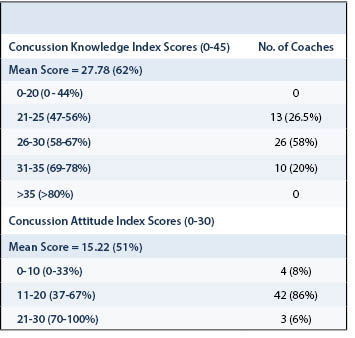

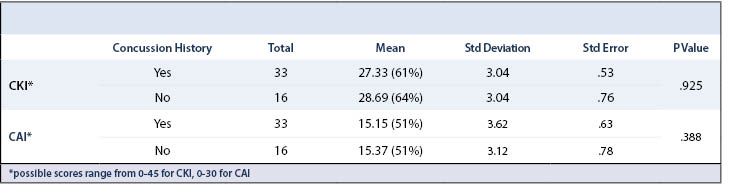

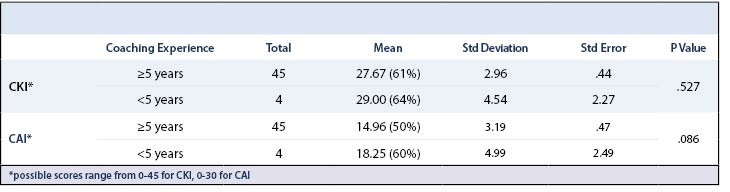

Averages were calculated for both CKI and CAI. The CKI average for the 49 coaches that were surveyed was 27.78 out of the 45 possible points which equates to an average score of 62% (Table 4). When stratified across coaches with and without past concussions, the averages were 61% and 64%, respectively. The same result was found when data was stratified by coaching experience (Table 5 and Table 6).

The mean CAI for coaches was 15.22 or an average of almost 51% for the coach’s attitudes towards concussions (Table 4). In considering what these numbers mean in the context of general attitudes towards concussions in women’s ice hockey coaches, an average 51% score in concussion attitudes represents an average attitude of uncertainty when it comes to making a stance on concussions. Similar results were seen when CAI was stratified across concussion history and coaching experience with no significant difference across any of the groups (Table 5 and Table 6).

This study demonstrated that 67.3% of coaches reported having had a suspected/diagnosed concussion themselves and of those, 24% of coaches did not report their concussions symptoms. There were no differences in CKI and CAI scores when comparing coaches with differing concussion history or length of coaching experience. Ninety-six percent of respondents reported “yes” to their institution having concussion management plans and concussion education. Athletes across varying populations are continuing to play while symptomatic from a concussive injury. Thus, the primary goal and eventual function of concussion education for athletes is to encourage honest and timely symptom disclosure.19 In line with this movement, many institutions at different levels of sport are requiring concussion education before the seasons begin for all players. The results from this study (Table 5 and Table 6) show strong data for the recommendation that coaches to be involved in player/athlete concussion education seminars, as this will only strengthen the coaches’ knowledge, regardless of their coaching experience or personal experience with concussions. The majority of U.S. states have passed legislation that requires concussion information to be provided to high school athletes and/or their parents prior to the athletes participation.20

In 2010, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) instituted a policy that requires all institutions to provide athletes with “informational materials about concussions” on an annual basis.19 More recently, in 2015, the NCAA initiated The Concussions Safety Protocol Review Process which encourages NCAA schools to submit concussion safety protocols to the NCAA sanctioned Concussion Safety Protocol Committee for review. These protocols are then measured to be consistent with the Interassociation Consensus: Diagnosis and Management of Sport-Related Concussion Best Practices.21 Despite having these proposals reviewed by one committee, all other decisions about content and how it is delivered is left up to the individual institutions which results in a high degree of variability in the materials that athletes receive.19 This continues to raise questions about what is the most effective method for education for collegiate athletes on concussion safety and reporting.21,22

There is limited data related to divisional differences in NCAA concussion incidence rates and education but Kerr et al. reported less concussion education and less compliance with baseline testing protocols in Divisions II and III schools compared with Division I programs.23 This is consistent with the studies previously mentioned that called for more accessible education materials for athletes, coaches, and athletic trainers. Ideally, there should be no discrepancy in safety materials provided based on division as well as sex and sport.It is important that decisions about how educational material is communicated to athletes is evaluated.19 The design and dissemination of concussion education have a direct effect on how the information is processed and received by the athletes. The goal of concussion education is to equip athletes with the right information to inform their decisions about reporting their own symptoms, if the time comes. However, it has been suggested that even when athletes are educated about concussions they still believe that a player with a concussion should play in an important game, such as a playoff final.24 This fact alone leads researchers to search for other factors that can affect a players decision to play through a head injury. In this case, coaches and their ability to influence their players is the focus of this study.

In the current study, the majority of the questions that evaluated coaches’ attitudes towards concussions were overwhelmingly partial to the views of an educated and supportive coach with a positive attitude towards the safe decisions that need to be made when concussion symptoms arise and/or persist. However, there were a few questions that resulted in a more diverse set of responses. The questions were scored on a Likert scale to measure to which degree a coach agreed or disagreed to the following statements:

- In general, I will do anything to win.

- Athletes aren’t as tough as they used to be.

- I think some athletes exaggerate concussion symptoms.

A study done by Kroshus et al. in April 2016 surveyed 325 collegiate athletes and found that most collegiate athletes receive concussion education from their athletic trainers but that many athletes (40.9%) would also like coaches to be involved in this process.19 This finding leads to the question this paper sets out to answer:

- What role do coaches play in athletes’ concussion education and symptom reporting?

While coaches are less “expert” in medical issues than athletic trainers and physicians, it is possible that athletes are indicating that in addition to the content of the safety information, they want to know that their head coaches as well as assistants and graduate assistants are informed and endorse the safety protocol as it is set out by the athletic trainer and team physician.19 In the current study, the 24% of collegiate women’s ice hockey coaches who did not report their own concussion symptoms is significant when considering where these coaches stand on concussion symptom reporting for their team and the model they set for the team culture. By having the coaches involved in this process, the staff portrays that everybody involved with the team is on board with the safety information being presented, and therefore, while perhaps unspoken, is encouraging and in full-support of a player reporting possible concussion symptoms with no repercussions.

Regardless of what role coaches have in the concussion education presentation, they play an important role in establishing a team’s culture, and with that, the team’s value of player safety.19

A 2014 study of a sample of collegiate football players found that a perception that the team coach would want his/her players to report their concussion was significantly associated with the likelihood that individual engaged in that safety behavior.25 In order to help facilitate a culture of safety within the team, coaches can verbally communicate their symptom reporting preferences, they could also, take part in the institutional concussion safety presentations. Additionally, coaches could receive specific concussion education aimed at recognizing symptoms of a concussion and understanding the consequences their athletes face if they continue to play after sustaining a concussion.

A primary limitation of the present study is the number of survey responses received from collegiate coaches. Due to the possibility that participating NCAA women’s ice hockey programs and coaches may be systematically different than non-responding programs and coaches, this response rate limits any generalizability to all collegiate women’s ice hockey coaches. The survey administered to coaches evaluated both their knowledge and attitude towards concussions as well as the concussion materials their institution has. As a result, recall bias raises issues of whether survey responses regarding coaches’ self-reported history of a diagnosed or suspected concussion and their prior reporting behaviors were based on initial knowledge and attitudes or recent education.

Overall, the coach surveys reflected that concussion education and culture is improving with increased attention from academia, popular news and the medical field. Ninety-six percent of NCAA institutions had a concussion management plan and education program. The average CKI was 62% and CAI was 51% for this study. The current study suggests that continuing to educate coaches, athletes and team medical staff may have the potential to prevent concussions as well as prevent continued play in symptomatic athletes.