Complicated Excision of a Large Upper Extremity Neural Fibrolipoma

Ryan Hoffman, MD, Mustfa K. Manzur, MPH, MS, Lee A. Kripke, MD, Katharine T. Woozley, MD

The authors report no conflict of interest related to this work.

©2022 by The Orthopaedic Journal at Harvard Medical School

CASE Fibrolipomas are a subset of benign lipomatous tumors typically found within the extremity musculature of adults between 40 and 60 years of age. They classically present as painless, slow growing, mobile masses characterized by diffuse adipose tissue with interspersed fibrous stroma on histology. Tumors of increasingly large size and symptomatology require complete work-up and excision to definitively rule out a malignant process. This case involves a 55-year-old female with a large mass over the right proximal volar forearm and associated sensory deficits. Radiographs demonstrated a radiolucent mass. MRI revealed a T1-weighted hyperintense and fat-saturated T2-weighted hypointense mass encasing the posterior interosseous nerve, a distal branch of the radial nerve. The surgical plan was modified intraoperatively when the mass was found to actually encase all three distal radial nerve branches. This excised mass was histologically consistent with a fibrolipoma measuring 9cm x 7cm x 4cm.

CONCLUSION Under certain circumstances, even the easiest surgical case can become very difficult. This fibrolipoma encased three critical neurovascular structures in the upper extremity excised without complication. This reflects the importance of two aspects of provider management:

- Systematic and meticulous physical examinations in the primary care setting to promptly identify aberrant pathology.

- Surgeon knowledge of anatomical variance in order to compensate for differences between gross examination in the operating room surgical field relative to previous imaging, especially in resource limited clinical settings.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE Level IV Case Report

KEYWORDSFibrolipoma; peripheral nerves; encasement; resection; excision; forearm

Lipomas of the extremities were first reviewed in the literature during 1936 with the first case report of lipomas occurring along the proximal forearm described in 1956.1,2 Lipomas are benign tumors of mature fat. They are the most common soft tissue tumors to occur in the extremities of adults.3 Lipomas are most common in individuals between 40 and 60 years of age. They typically occur superficial to the fascia and present as mobile and painless masses. Rarely, lipomatous masses may be immobile and involve muscle(s) associated with the structure, presenting deep to the fascia, either inter- or intramuscularly. Fibrolipomas are a subset of lipoma differentiated by increased fibrous tissue and septae seen both macroscopically and histologically. Fibrolipomas are most commonly noted as superficial masses, however they can rarely be found inter- and intramuscularly. Standard-of-care treatment of symptomatic fibrolipomas is marginal resection. Like non-differentiated lipomas, fibrolipomas respond similarly to surgical intervention with a limited rate of recurrence. If asymptomatic, these tumors may be treated non-operatively with observation alone.3,4 Evaluation of soft-tissue masses requires taking a careful history, detailed physical exam, appropriate imaging, and histological work-up upon excision.3,4 Superficial masses ≥5cm and those deep to the fascia should undergo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation.4-7 Lipomatous masses are typically T1-weighted hyperintense masses equal in density to surrounding subcutaneous fat. T2-weighted fat-suppressed imaging generally suggests the presence of a hypointense mass.4 For patients with rapidly growing and symptomatic masses suspected of being lipomatous, marginal resection is offered, especially in the setting of cosmetic or physical impairment.4-7 The incidence of recurrence in benign lipomatous lesions is <5% and extensive follow-up is rarely required. However rare, malignant presentations of lipomatous lesions (i.e. liposarcomas) approach nearly a 100% recurrence rate and require multimodal management over time to address local and potential metastatic masses.4 This case involves a 55-year-old female with an intramuscular giant fibrolipoma of the proximal forearm completely encasing local radial nerve branches which was causing sensory impairment without concomitant motor deficits.

A 55-year-old right-hand-dominant female who presented to our hospital’s orthopedic surgery ambulatory care clinic. She reported a one-year history of a slowly growing mass located in the right forearm. The patient endorsed decreased range of motion about the elbow and paresthesia over the dorsum of the hand in the distribution of the superficial radial sensory nerve; the patient rated this pain as a five out of ten on the numerical pain rating scale . Physical therapy had yielded minimal improvement of symptoms. Past medical history was significant for hypertension, obesity, and bilateral shoulder rotator cuff tendinopathy. Past medical and family medical histories did not include cancer. Social history was noncontributory to this case.

On physical exam, the patient was noted to have a 10cm x 9cm immobile, non-tender mass on the proximal volar aspect of the right forearm, immediately distal to the flexion crease of the elbow joint. Range of motion at the elbow appeared limited due to mechanical obstruction during flexion. She was found to have paresthesia in the distribution of the superficial radial nerve. The remaining sensory, motor, and vascular exam of the right upper extremity were within normal limits. Due to the size, location, and immobility of the mass, MRI with contrast was ordered and reviewed with the patient during scheduled follow-up.

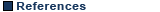

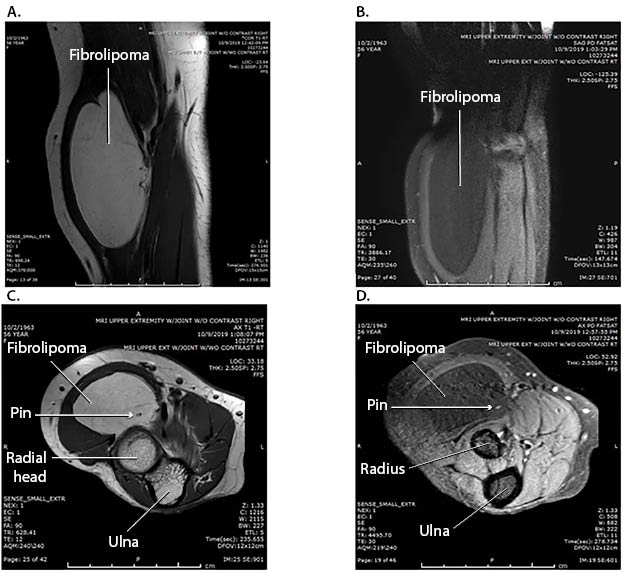

Radiographs of the right elbow revealed a radiolucent mass over the proximal volar forearm near the elbow without evidence of dislocation or bony involvement (Figure 1). MRI further demonstrated an intramuscular soft tissue tumor encircling the radial and posterior interosseous nerves in the radial tunnel. T1-weighted and fat-saturated T2-weighted hypointense images were significant for a hyperintense and hypointense proximal volar mass, respectively. There was no post-contrast enhancement (Figure 2). Combined with clinical features, the MRI findings were suspicious for a soft tissue intramuscular lipomatous tumor located within the radial tunnel.

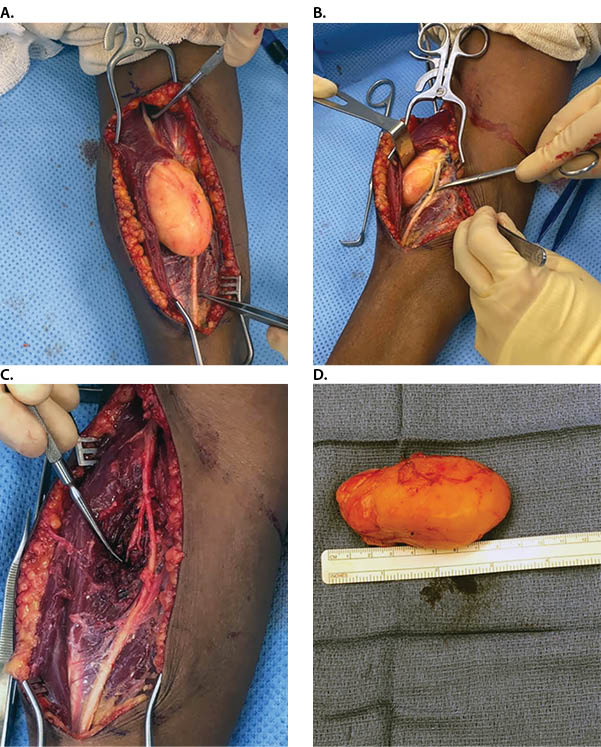

The patient elected to receive a peripheral nerve block and undergo surgical exploration and excision of the mass to address functional and cosmetic concerns associated with the mass. In the operating room, a volar Henry approach was performed to establish proximal and distal control of the radial nerve branches. Dissection confirmed the presence of a 9cm x 7cm x 4cm yellow, soft intramuscular soft tissue mass within the radial tunnel encasing three nerves: radial superficial sensory, posterior interosseous, and radial nerve proper. Encasement of the radial superficial sensory nerve was not observed on any imaging preoperatively nor was it anticipated during perioperative planning, thus electroneurography equipment was not available at the time of surgery to provide additional assurance that this delicate terminal structure was preserved. Surgery proceeded with blunt dissection until successful excision could be performed (Figure 3). To ensure relief of nerve pain symptoms, radial tunnel decompression of the radial nerve proper, posterior interosseous, and radial superficial sensory nerves was then performed prior to closure. Neurolysis of the decompressed nerves was also utilized as a pain management adjuvant. Afterwards, the wound was closed in three layers and the mass was sent as an excisional biopsy specimen to pathology for gross and histological analysis. Gross pathology indicated 60g tan-red, lobulated, glistening fatty tissue. Serial sectioning and histology indicated a homogenous tissue demarcated by the broad fibrous bands. The patient reported being pain free post-operatively and was discharged on the same day. She remained free of pain in her right forearm during periodic follow-up over the next six months.

The patient was found to have a large immobile mass with MRI imaging and surgical exploration leading to the identification of a benign lipomatous tumor encasing all branches of the radial nerve immediately distal to the elbow. Approximately 1.8% of lipomas are intramuscular and there are even fewer studies reporting large intramuscular lipomas in the proximal forearm.3-6,8,9 Lipomas specifically present in the volar, proximal forearm, near the radial nerve have been reported.7,9,10 However, very few examples in the literature report encasement of any radial nerve branches.9 This 9cm x 7cm x 4cm fibrolipoma complicated by complete encasement of all radial nerve branches of the proximal forearm is among the largest reported lipomatous tumors in the upper extremity.3,5,6,11

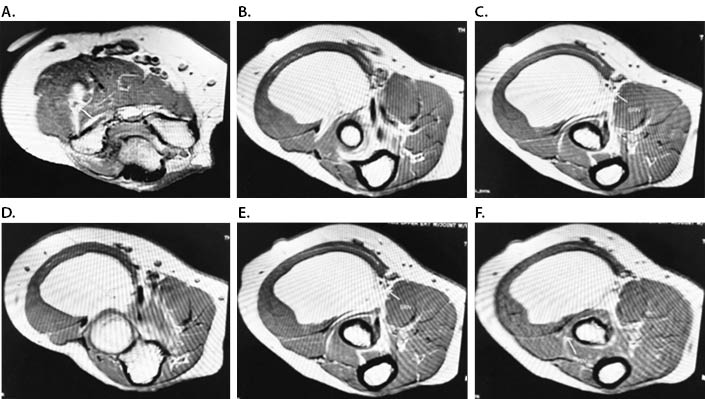

Patients with lipomatous tumors presenting with compressive neuritis in an extremity frequently present with motor deficits impacting the forearm extensors before (secondary to physical compression by the mass) or after surgery (via iatrogenic injury).8,9 Furthermore, upper extremity compressive neuritis generally presents in the median nerve distribution.2,9 Nerve encasement of the radial superficial sensory nerve was not detected on imaging nor was it presumed during the perioperative planning process (Figure 4). Interestingly, despite complete encasement of the radial nerve branches, both pre-post-operative motor deficits were not observed in this case. This reflects the importance of two important aspects of provider management:7

- Systematic and meticulous physical examinations in the primary care setting to promptly identify aberrant pathology before it causes downstream health challenges

- Surgeon knowledge of anatomy in order to compensate for differences between gross examination in the operating room surgical field relative to previous imaging utilized for diagnosis and procedure planning

Even the easiest case can become very difficult under certain circumstances. While careful surgical technique enables maximal preservation of neurovascular structures, because of this case, the authors recommend consider keeping electroneurography (EMG) equipment readily available in all large lipomatous tumor removal surgeries to limit the risk of iatrogenic injury during dissection and resection. EMG is commonly utilized in removal of lipomatous masses involving spinal structures.12 However, having EMG available for any large lipomatous masses likely involving neural structures may be a risk averse patient-centric surgical approach when MRI imaging is either not possible or involves equipment with limited resolution. The superficial branch of the radial nerve has a diameter typically between 0.8mm-2.0mm and the posterior interosseous nerve has a diameter between 0.8mm and 3.1mm.13 Current standard of care involves utilization of 3.0T MRI scanners to image structures, however the maximum resolution of the 3.0T MRI scanner is 2.0mm x 2.0mm.14 Therefore, it may not always be possible to capture distal nerve entrapment if nervous structures do not have a broad enough caliber.

Definitive pre-operative identification for the location of a lipomatous mass requires MRI imaging. The size of the tumor in this case and its proximity to the radial nerve branches along the volar aspect of the forearm demonstrate the importance of MRI imaging and tissue biopsy in making the appropriate diagnosis and treatment.5,7 Had the tumor been composed of encapsulating sarcomatous tissue, radiation and/or subsequent wider surgical excision would have been warranted. A broader histological workup would have been required to evaluate the malignant nature of the tumor.4,6,15