Peter Waters, MD

George S.M. Dyer, MD

Here’s how I met the world-famous Dr. Peter Waters: In 1999, we were paired up as the two slowest guys in an early-morning sculling camp. The coach wanted to keep us out of the way of the young Olympic hopefuls and seriously competent scullers who’d signed up for a week of Spring mornings for technical tips. We hit it off, so after the camp ended we agreed to meet the next week, an hour earlier. No one else uses the boathouse at those hours, so conversations before and after rowing were completely private, and they became astonishingly personal. Our marriages. Peter’s kids. Our life struggles, manifested in the ups and downs of our (still mediocre) sculling. As “next week” turned into all Summer, and then Fall, then the next year, Peter became the kind of friend you only make once or twice in a lifetime, if you’re lucky.

Here’s what never came up: Work. I know it’s hard to believe, but we rowed together several times a week for two years before that seemed relevant. One morning in my 3rd year of med school I came to row dressed in scrubs for my surgery rotation, and we had a conversation that now seems comical.

“Why are you in scrubs?”

“I’m a medical student.”

“Really? I’m a doctor.”

“Really? What kind?”

“An orthopaedic surgeon.”

“Really? I’m thinking of applying in orthopaedic surgery…”

In that instant, our beautiful friendship broadened into the defining mentoring relationship of my life. It turned out that my rowing buddy was kind of a big deal orthopaedic surgeon—Peter Waters’ contributions to Boston Children’s Hospital, to Harvard, and to orthopaedic surgery, are as numerous as they are profound.

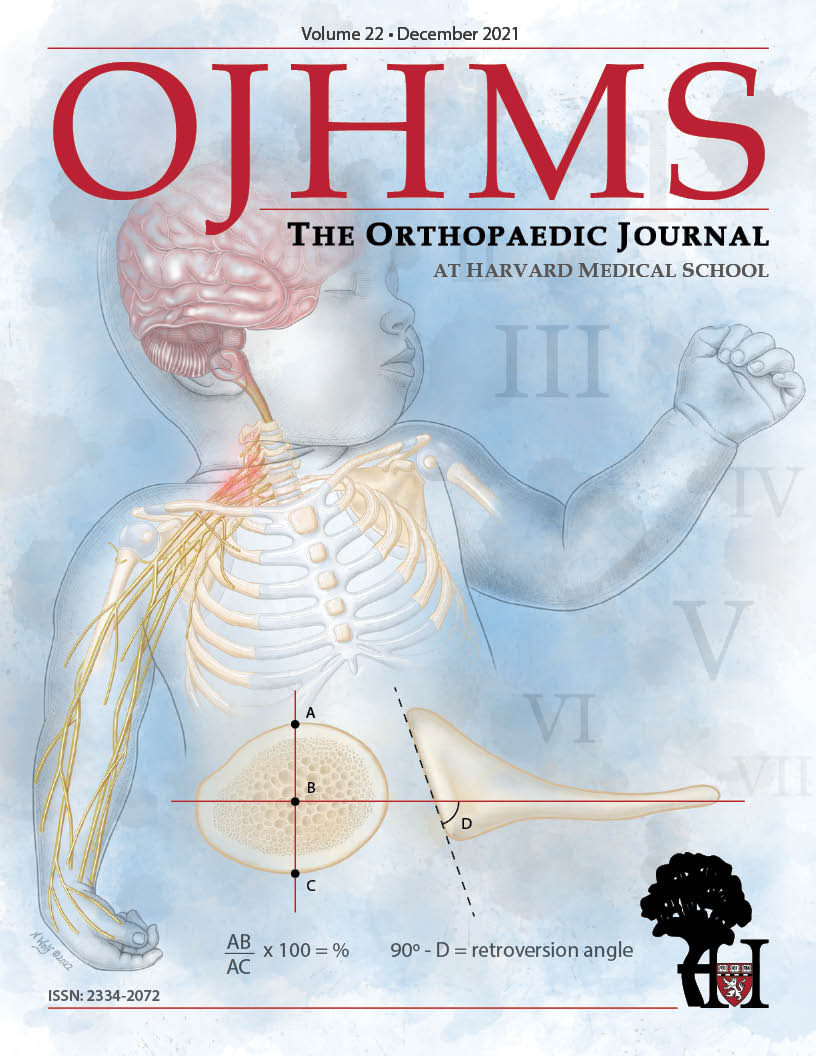

Here’s just one: His pioneering work in understanding brachial plexus birth injuries. Dr. Waters helped us to recognize these are not static injuries, that the growing skeleton is deformed by the imbalance of paralyzed muscles, and—crucially—that the deformity can be corrected by surgery to rebalance muscles early enough. At Children’s, Dr. Waters built a division of upper extremity surgery and then continued the building of a world-leading department. His formula has been simple: he’s insisted on the principle that great care of complex children’s problems requires complete commitment to those children, from the staff and from the institution.

Principled commitment. In this, Peter Waters has led by example.

Meeting him in the first place was an accident, but I’ve been very deliberate about learning from Peter’s example ever since. I’ve been fortunate to work and train with him as a medical student, then as an orthopaedic resident, then as a fellow, now as a colleague. Twenty years later, I find I’m still actively parroting things I’ve heard him say or seen him do. Technical tricks. Ways of explaining things to patients. How to break down a complicated problem—in surgery or in life—into manageable parts.

Principled commitment. Those who’ve worked with Peter Waters will tell you that’s not always the most comfortable thing to be around, particularly at close range. It’s more of a full-contact, high-expectations thing. He’s created opportunity for me, and then made sure I used it well. He’s questioned and he’s nudged. He’s encouraged and he’s sometimes criticized, as a committed friend and mentor should do. I’m trying to follow that example, too, as I’ve grown more senior and I try to mentor people myself.

Principled commitment. Those who’ve worked with Peter Waters will tell you that’s not always the most comfortable thing to be around, particularly at close range. It’s more of a full-contact, high-expectations thing. He’s created opportunity for me, and then made sure I used it well. He’s questioned and he’s nudged. He’s encouraged and he’s sometimes criticized, as a committed friend and mentor should do. I’m trying to follow that example, too, as I’ve grown more senior and I try to mentor people myself.

My story with Peter Waters is remarkable, but I know it’s not unique. I’m pretty sure Don Bae has a similar story to mine—only his starts on a basketball court. Countless others have been touched in similar ways, and most everyone around Children’s Hospital, or Harvard orthopaedics, has a “Peter Waters story,” or two, they could tell. One of Peter’s many gifts is his uncanny ability to find people, whether or not they realize they need finding, and to help them become their best selves.

Accordingly, it is my bittersweet task to help dedicate this issue of the Orthopaedic Journal at Harvard Medical School to my friend, Peter Waters.

Peter: even though you’re not really retiring, and even though you’ll be coming back to Harvard from time to time and staying engaged, this is a good moment to say, “Thank you.” You have helped us all to become better, and we will miss you.

George S.M. Dyer, MD

Program Director, Harvard Combined Orthopaedic Residency Program

Associate Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery, Harvard Medical School