Return to Play Following High-Grade Turf Toe Injuries in National Football League AthletesBiomechanical Comparison of Arthroscopic SMC Knot Constructs

Benjamin B. Lindsey, MD, Neil K. Bakshi, MD, Kempland C. Walley, MD, David M. Walton, MD, James R. Holmes, MD, Paul G. Talusan, MD

©2021 by The Orthopaedic Journal at Harvard Medical School

BACKGROUND Return-to-play (RTP) rates of National Football League (NFL) athletes following operative intervention for numerous foot and ankle injuries has been reported. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the RTP rates in NFL athletes who sustained high-grade turf toe injuries. We hypothesized that NFL athletes requiring operative intervention for high-grade turf toe injuries would have lower RTP rates and longer recoveries than athletes treated nonoperatively.

METHODS Public press releases, team sites, biographies, and injury reports were reviewed to identify athletes who sustained high-grade turf toe injuries, as indicated by operative intervention or missed playing time of 2 weeks or more. RTP was defined as the ability of an athlete to return to full competition. Athletes were excluded if RTP was prevented for reasons unrelated to the injury. Demographic and performance data were obtained and analyzed.

RESULTS Fifty-three NFL athletes were identified with high-grade turf toe injuries that met inclusion criteria. Twenty-eight of these athletes were treated nonoperatively and 25 were treated operatively. The overall RTP rate was 91% (48/53). Athletes who were treated nonoperatively had a RTP rate of 100% (28/28) while athletes treated operatively had a RTP rate of 80% (20/25). The mean time to RTP for all athletes was 140.9±111.9 days. The mean time to RTP for nonoperatively treated patients was 75.8±99.0 days, compared with 221.4±81.6 days for operatively treated athletes.

CONCLUSION Following operative intervention for high-grade turf toe injuries, only 80% (20/25) of NFL athletes achieved return to play. No athletes were able to return the same season as operative intervention and the mean time to RTP following initiation of treatment was significantly shorter for players who underwent nonoperative management.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE Level III Retrospective Cohort

KEYWORDS Turf toe; plantar plate; National Football League; NFL; forefoot return to play

Turf toe is a common injury, particularly among high level football players.4 These injuries were first described in 1976 in collegiate football players at the University of West Virginia as a hyperextension injury to the plantar plate of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint. They noted an incidence of 5.4 turf toe injuries per season.1 A survey of 80 athletes in the National Football League (NFL) found that 45% had sustained turf toe injuries previously.2 This injury was originally described in athletes competing only on artificial surfaces, but a later study demonstrated that turf toe occurred equally among athletes participating on modern artificial turf and natural grass.3 These injuries can seriously impact an athlete’s career, with some never returning to their same level of activity.4

There is little innate bony stability of the first MTP joint. The majority of stability is provided by the capsular ligamentous complex, comprised of the capsule, the plantar plate, the collateral ligaments, the adductor and abductor hallucis tendons, and the short flexor complex (which includes the flexor hallucis brevis and the sesamoids embedded in the brevis tendons).5 Football players are at risk for this injury as they frequently sustain an axial load to a plantarflexed ankle, driving the hallux into hyperextension. This results in injury to the capsular ligamentous complex.6 Following this hyperextension moment to the first MTP joint, a varying degree of damage occurs. This ranges from a mild sprain of the first MTP plantar plate to frank tearing of the plantar plate.7 These tears can be associated with fractures of the sesamoid bones and if there is a valgus component to the vector of force during injury, a traumatic bunion can occur.8 Turf toe injuries can also occur via hyperflexion and frank dislocation mechanisms.6

Turf toe injuries are graded via a classification system described by Clanton.9 Grade 1 injuries involve attenuation of the plantar structures of the first MTP joint and athletes may return to play as tolerated +/- taping or modified athletic shoe wear. With grade 2 injuries, there is partial tearing of the plantar plate. Athletes typically require rest from sport along with anti-inflammatory medications and possible immobilization. These injuries frequently respond to nonoperative measures. With grade 3 injuries, there is complete disruption of the plantar plate and players require either prolonged immobilization or operative intervention.5,6 Fortunately, the majority of turf toe injuries respond to nonoperative management. In one series over the course of 6 collegiate football seasons, only 1.74% of turf toe injuries resulted in operative intervention.10

Following any orthopaedic intervention, some NFL athletes are unable to return to their prior level of performance. In one series, 79.4% of NFL athletes returned to play (RTP) following a variety of orthopaedic operative intervention.11 While the RTP rate following operative intervention for many orthopaedic foot and ankle injuries is well documented in NFL players, including Achilles tendon ruptures, ankle fractures, and Jones fractures, there is scant data on the RTP rate in NFL athletes following operative management for turf toe.11-13

The goal of this study was to evaluate the RTP rate in NFL players who sustained high-grade turf toe injuries, specifically examining the differences in RTP between athletes treated nonoperatively versus operatively. We hypothesized that NFL athletes undergoing surgery for high-grade turf toe injuries would have lower RTP rates and experience longer recovery time than athletes treated nonoperatively. Additionally, we hypothesized no difference would be found between NFL athletes treated nonoperatively and operatively with respect to athletic performance metrics once those athletes had returned to competition.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study in which NFL athletes with a history of a turf toe injuries sustained while playing professionally between the 2000 and 2017 NFL seasons were identified. These athletes were identified via methods demonstrated in prior studies that utilized publicly available NFL injury data including public press releases, team sites, biographies, and/or injury reports.11-18 Players on an NFL roster were included in the study if they had been drafted into the NFL and played in at least 1 preseason or regular season game prior to sustaining a turf toe injury. Additionally, to ensure only high-grade turf toe injuries were included, athletes had to either miss 2 or more weeks of play or undergo operative intervention to be included. Documentation of a turf toe injury or operative intervention for turf toe was required from 2 separate sources. Player identification and data abstraction was performed and validated by 2 authors. NFL athletes who sustained turf toe injuries prior to the year 2000 were excluded to maintain consistent nonoperative management and operative techniques. NFL athletes who were injured after the end of the 2017 NFL season were excluded because of an inadequate amount of time for RTP. Athletes were also excluded if their RTP was prevented for reasons unrelated to the injury such as suspension, unrelated injury, or personal matters.

Data collected included age, NFL position, injury, date of injury, date of surgery, RTP status, time to RTP, number of games played the season after injury, position-specific performance measures (from the season prior to injury through the second season after injury), and any accolades a player received. Successful RTP was defined as participation in at least 1 play in a preseason or regular-season NFL football game after initiation of treatment for a turf toe injury. Return to play in other professional sports leagues, such as the Arena Football League, was not considered RTP. The first preseason or regular season game a player participated in was regarded as the date of RTP. Return to prior level of performance was defined as a player’s postinjury statistical performance exceeding 80% of his preinjury statistical performance. This was achieved by comparing a player’s most relevant statistical category (passing yards, receiving yard, rushing yard, total tackles, return yards) from the season before treatment for turf toe to the season following treatment of turf toe (Appendix 1*). Of note, since detailed patient data was not available, it is impossible to delineate whether all injuries were in fact high grade. As a result, authors considered it invalid to statistically compare outcomes (e.g. RTP) between nonoperative and operative groups, given likely heterogeneity in study cohort. To put it in simpler terms, comparing the two groups would be intended to observe the effect of surgery on RTP however, both groups may have not met the criteria for surgery to begin with. For purposes of comparison, categorical variables, including comparisons of proportions, were compared using Fischer’s Exact Test with statistical significance defined as P< 0.05.

A total of 53 NFL athletes were identified who met the study inclusion and exclusion criteria. Initially, 39 NFL players were identified who underwent operative intervention for a turf toe injury. Fourteen of these players were excluded (10/14 excluded due to inadequate publicly available information on the specific date they underwent surgery, 3/14 excluded as their injuries occurred during the 2018 NFL season, 1/14 excluded due to sustaining simultaneous bilateral turf toe injuries). On the other arm, 42 NFL players were identified with turf toe injuries treated nonoperatively. Again, 14 of these players were excluded (9/14 excluded due to inadequate publicly available information on the specific date they were injured, 5/14 excluded because they did not miss any games for their injuries thus indicating a potential low-grade injury).

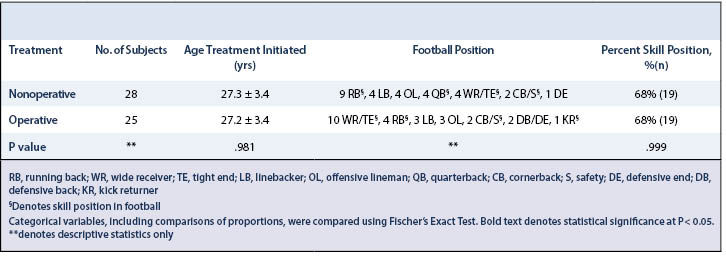

Twenty-eight (53%) of these athletes underwent nonoperative management, requiring at least 2 weeks of rest, and 25 (47%) of these athletes underwent operative intervention. In those who underwent nonoperative management, 21 (84%) were primarily offensive players and 7 (16%) were primarily defensive players. Four of the athletes (14%) were offensive/defensive lineman, while the remaining 24 athletes (86%) were non-lineman. In those who underwent operative management, 17 (68%) were primarily offensive players, 7 (28%) were primarily defensive players, and 1 (4%) was primarily a special-teams player. Three of the athletes (12%) were offensive/defensive lineman, while the remaining 22 athletes (88%) were non-lineman. In both groups, 68% of athletes can be characterized as skill positions (Table 1). Average age of athletes in the surgical group was 27 years (range 21 – 33) and the average age in the non-operative group was 27 (range 22 – 36).

The overall RTP rate after high-grade turf toe injuries was 91% (48/53) (Table 2; denoted via average ± standard deviation). Athletes who underwent nonoperative management of a high-grade turf toe injury had a RTP rate of 100% (28/28) while athletes who required operative intervention had a RTP rate of 80% (20/25) (P = 0.011). Mean time for RTP for all 53 athletes was 140.9 ± 111.9 days. The mean time for RTP for athletes who underwent nonoperative management was 75.8 ± 99.0, compared with 221.4 ± 81.6 for athletes who underwent operative management (Table 3).

Of all athletes who sustained high-grade turf toe injuries, only 45% (24/53) were able to RTP during the season treatment was initiated. While 86% (24/28) of athletes who underwent nonoperative management were able to return to play the same season treatment was initiated, 0% (0/25) athletes who underwent operative management were able to return the same season (P$le;0.0001). In regard to RTP during the season immediately after initiation of treatment, of all athletes who sustained high-grade turf toe injuries, 85% (45/53) were able to achieve RTP the season immediately following treatment initiation. Of these players, 96% (43/45) were considered ready and acceptable to play or available in week 1. Eighty-nine percent (25/28) of athletes who underwent nonoperative management were able to achieve return to play the season following initiation of treatment, while 80% (20/25) of operatively treated athletes were able to return to play. The season following treatment initiation, athletes who underwent nonoperative management and achieved RTP played in 82% (315/384) of possible regular season games while athletes who underwent operative management and achieved RTP played in 86% (275/320) of games.

Of all NFL athletes other than offensive/defensive lineman who achieved RTP the following season, 55% (18/33) were able to return to their prior level of performance. 78% (14/18) of the NFL athletes who underwent nonoperative management were able to return to their prior level of performance while only 27% (4/15) who underwent operative management were able to return to their prior level of performance (Table 4, P=0.032).

A sparse amount of RTP information exists in the literature regarding turf toe injuries. A small series in 1978 described 3 collegiate athletes who underwent delayed operative intervention following failed nonoperative management of turf toe. Two of the players, 1 football player and 1 basketball player, returned to their prior level of activity, but 1 additional football player was unable to return to collegiate football. Three other collegiate football players were treated nonoperatively in the series and were able to return to collegiate football.19 Another small series described 4 Division I football players who underwent operative treatment of turf toe injuries. All 4 returned to Division I football, though one aggravated his injury during the subsequent football season and was held from contact activities for 6 weeks.20 Drakos et al. reported on 2 Division I football players who underwent operative intervention following complete disruptions of the first MTP plantar plate. Both athletes were able to return to football 6 months following surgery. A 3rd athlete in their series had an 80% plantar plate rupture on MRI, was treated nonoperatively, and was able to return to full-contact football.21 In a larger series, Anderson summarized 19 collegiate and professional athletes who were treated for turf toe. Nine of the athletes in his series underwent operative repair and all but 2 patients returned to full athletic activity. The 2 athletes who were unable to return to their prior activity level were both professional football players who were treated operatively. Overall the series demonstrated a 78% RTP rate among patients treated operatively.4 More recently Covell et al. reported the results from operative treatment of specifically traumatic hallux valgus in athletes. Twelve NFL players were included in the series of 19 athletes and overall a 74% RTP was reported.22 In another large series, Clanton et al. detailed 51 Rice University football players who sustained injuries to the first MTP joint, with only 1 requiring operative intervention while the rest were treated nonoperatively. All patients returned to play with missed playing time ranging from 0 to 56 days.9 Finally Smith and Waldrop recently reported on 14 competitive football players who were treated operatively for grade 3 turf toe injuries. Eleven of fourteen players returned to competitive football. The 3 who did not return to competitive football did not return due to reasons unrelated to their injuries. The 11 players who did return missed an average of 16.5 weeks of playing time.8 Overall, the current literature demonstrates a consistently high RTP rate for athletes who undergo nonoperative management of turf toe injuries. The literature is mixed in regard to RTP following operative intervention. Multiple small series and Smith and Waldrop’s larger series, report a 100% RTP rate. This is contrasted by Anderson and Covell’s series, demonstrating a 79% and 74% RTP rate respectively.

The results from our current study, with a RTP rate of 100% in NFL athletes who underwent nonoperative management of high-grade turf toe injuries, corresponds to the previously reported high RTP rates with nonoperative management. The RTP rate of 80% among operatively treated NFL athletes is similar to the rate of 79% published by Anderson, and thus presents a less successful RTP rate than other series previously reported. This finding is consequential, as 1 in 5 NFL athletes who require operative intervention for turf toe will not achieve RTP. It is important to note that though described as high grade, less severe injuries are managed nonoperatively and that heterogeneity may exist between injury characteristics of those in nonoperative and operative study arms.

Again, though subject to possible heterogeneity between severity of injury between groups, our results highlight the difference in time to successful RTP between conservative management and operative intervention, 75.8±99.0 days versus 221.4±81.6 days respectively. No players were able to achieve RTP during the same season they had surgery. Subsequently, NFL athletes need to be aware that operative intervention for turf toe is typically a season ending procedure. Additionally, our results are notable for the significant difference between nonoperative and operative management in athlete’s, outside of offensive/defensive lineman, ability to return to their prior level of performance. Only 27% (4/15) of non-lineman athletes were able to return to their prior level of performance the season after operative management, indicating recovery from operative intervention for turf toe injuries lasts far beyond when a player returns to the playing field.

In regards to other foot and ankle injuries commonly sustained by NFL athletes, Jack et al. demonstrated a 72.4% RTP rate following Achilles tendon repair, Mai et al. demonstrated a 78.6% following open reduction and internal fixation of an ankle fracture, and Lareau et al. demonstrated 100% RTP following acute Jones fracture fixation.11-13 Thus, the RTP of 80% following operative intervention for turf toe demonstrates that while it is not as career ending as some foot and ankle injuries, it is still much more impactful than other serious injuries.

This study has multiple limitations. First, the retrospective nature of this study introduces bias simply through the study design. Additionally, the use of public press releases, team sites, biographies, and injury reports information to identify turf toe injuries and operative intervention for turf toe injuries is prone to numerous biases and flaws. These include selection, reporting, and observer bias. In the attempt to compare outcomes (e.g., RTP and performance) within two treatment groups of high-grade turf toe injuries, the most profound of source of bias is selection bias as it is reasonable that players undergoing surgical management may have a higher-grade injury than those treated nonoperatively. Furthermore, the conclusions drawn in this study must be interpreted with a degree of caution as this selection bias may limit the strength in comparison of treatment outcome strategies of high-grade turf toe injuries. Definitions of high-grade turf toe injuries are often nebulous, therefore our authors elected to define turf-toe injuries has those players who either missed 2 or more weeks of play secondary to their injury or underwent operative management. As this criterion has not yet been reported, and underscores a possible source significant bias, we had decided to temper our conclusions without statistical comparison.

Inherently, the athletes in the study were treated at numerous institutions by various surgeons utilizing differing operative techniques. Given this format for data collection, the specific details of each athlete’s injury and the nonoperative treatment protocol versus specific operative technique each athlete underwent was not known. Additionally, pre and postoperative rehabilitation protocols were not known or standardized amongst players. Thus, the overall study design results in multiple unknown confounding variables. Another limitation to our study was its size, as only 53 athletes were identified who met inclusion and exclusion criteria. This small size introduces sample size bias. Finally, as this study defined RTP as game play in the NFL, it does not include athletes who were able to return to other professional football leagues.

Regardless of these limitations, this study is the largest overall investigation of high-grade turf toe injuries. Additionally, it is the largest report of operatively treated turf toe injuries. Subsequently, this study is able to provide important prognostic information to elite athletes who sustain a high-grade turf toe injury. This study demonstrates that a significant number of athletes who require operative intervention for turf toe are unable to return to the same level of athletic activity. Additionally, this study reveals that among athletes who achieve RTP following operative intervention for turf toe injuries, their overall performance may be significantly worse than prior to sustaining the injury.

Following nonoperative management of high-grade turf toe injuries, 100% (28/28) of athletes have returned to the NFL, while following operative intervention only 80% (20/25) have returned (P = .011). No athletes were able to return the same season, as surgery and the mean time to RTP following initiation of treatment was significantly shorter for players who underwent nonoperative management. Postoperative performance was significantly (P = .032) worse in players who underwent operative intervention compared to nonoperative management. This study provides important prognostic information to high level athletes on recovery following high-grade turf toe injuries.